Decoding Philippine Mythology

Philippine mythology stands as a testament to the cultural richness of the archipelago, encapsulating a myriad of gods, goddesses, and mythical creatures. However, delving into the heart of these narratives is an endeavor best undertaken by Filipino people who speak the languages of the Philippines. This linguistic and cultural voyage unveils the inherent complexities that resist easy translation into English, requiring a nuanced understanding rooted in the diverse linguistic landscape of the islands.

Linguistic Diversity as a Gateway:

The Philippines boasts a linguistic diversity that surpasses 170 languages and dialects, each carrying its own unique cultural nuances. This linguistic diversity is not merely a collection of words; it is a key that unlocks the intricate tapestry of mythological narratives, each woven into the linguistic fabric of specific communities.

Connected Mythologies

All the stories and myths in the Philippines are connected because they all come from the same group of islands. People talk to each other, share ideas, culture, and words, and that's how these stories get passed down from one generation to the next.

Differen versions of the same story

Same stories when verbally passed down created different versions, The existence of diverse narrative interpretations can be attributed to the oral transmission of stories, as the process of verbal communication often leads to varied translations and interpretations.

Untranslatable Nuances:

Many characteristics and ideas embedded in Philippine mythology resist straightforward translation into English. The intricate web of beliefs, rituals, and metaphors that define these myths often relies on Filipino idioms, expressions, and linguistic nuances that might lose their depth and resonance when translated. Concepts like "kapwa" (shared identity) or "pakikipagkapwa-tao" (social relations) carry layers of cultural meaning that elude easy translation.

Comparisons to Hinduism and Buddhism:

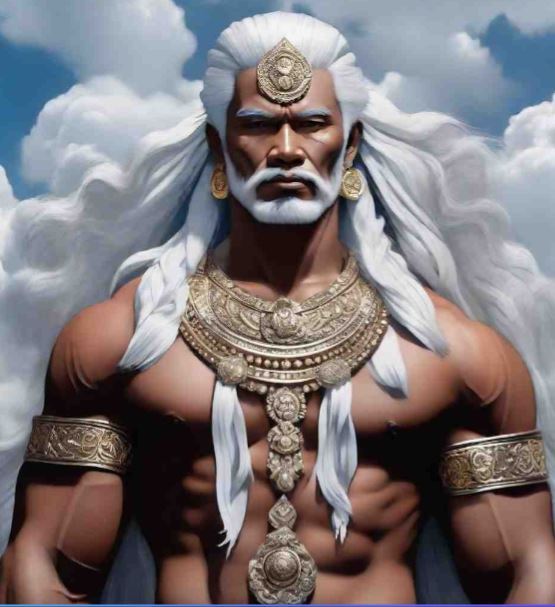

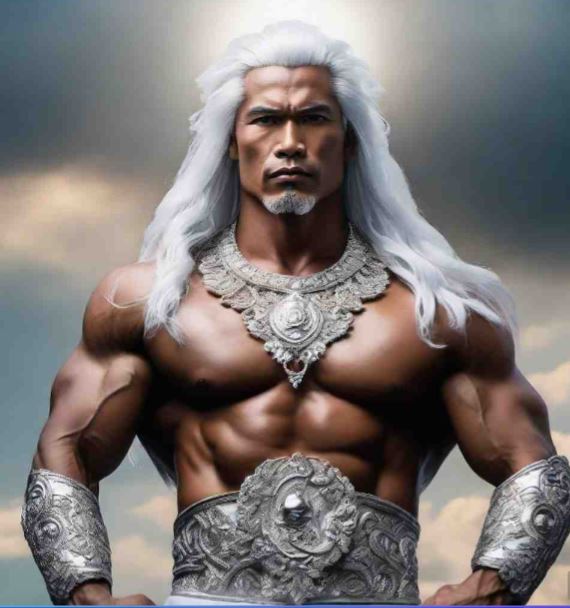

Despite the allure of equating Philippine mythology with European perspectives, a more insightful comparison emerges when juxtaposed with Hinduism and Buddhism. The influence of Indian culture, evident in ancient trade routes and cultural exchanges, has left an indelible mark on Philippine mythology. Understanding the shared threads between these Southeast Asian cultures allows for a deeper appreciation of the interconnectedness of beliefs and practices.

Philippine mythology, a vibrant tapestry of gods, goddesses, and mythical creatures, has captivated the imaginations of locals for centuries. However, for foreigners who do not speak the languages or fully comprehend the intricacies of Filipino culture, unlocking the depths of this mythological realm can be a challenging and nuanced endeavor. Several factors contribute to the difficulties faced by outsiders, ranging from linguistic barriers to cultural subtleties that elude easy comprehension.

Oral Transmission as a Living Tradition:

Philippine mythology is not confined to dusty tomes but thrives as a living, breathing tradition passed down orally through generations. This oral transmission ensures that the essence of the stories remains intact, with storytellers adding their own nuances and interpretations. Foreigners looking through a European lens may miss the dynamic nature of these narratives, intertwined with the daily lives of the Filipino people.

Philippine mythology as a living Mythology'

the reason why so many stories in the Philippines have different

versions is because there are so many languages and people and it transforms as

it us orally passed down. as it was in ancient times, The mythology in the Philippines

is a living one, unlike in Europe or Western countries where mythology is already dead.

Philippine mythology is alive compared to the dead mythology in most Westernized countries. So many variation of stories and mythology same as the multitude of languages and dialects reflects Philippines's lengthy and diverse history. Same as it's language mythology evolves spreading all over the archipelago and each island owning and evolving its own unique version of it.

Compared to the dead mythology in most Westernized countries the Mythology of the Philippines is alive. Unlike mythology relegated to dusty tomes in Europe, Philippine mythology thrives as a living tradition passed down orally through generations. This oral transmission ensures the stories remain dynamic, with storytellers infusing their interpretations and nuances into the narratives. This living tradition is a stark contrast to the static nature of mythology in Western countries.

Cultural Contexts in Mythological Names:

The names of gods, goddesses, and mythical beings in Philippine mythology often carry specific cultural contexts and linguistic significance. Attempting to translate these names into English may lead to a loss of the deeper meanings and cultural resonances encapsulated within the linguistic roots of these stories.

Beyond the Eurocentric Gaze:

Foreign perspectives on Philippine mythology often fall prey to Eurocentric interpretations, missing the unique cultural and linguistic nuances. Rather than approaching these myths through a European lens, a more illuminating exploration involves recognizing the indigenous perspectives and influences that have shaped these narratives over centuries. with excemption to foreign Anthropologist (who have studied and learned can speak and fully comprehend the language).

Linguistic Diversity as a Barrier:

One of the primary challenges faced by foreigners delving into Philippine mythology is the vast linguistic diversity of the archipelago. With over 170 languages and dialects spoken, each carrying its unique cultural nuances, grasping the full spectrum of mythological narratives becomes a linguistic odyssey. Concepts and ideas embedded in the myths may rely on Filipino idioms, expressions, and linguistic subtleties that are often lost in translation, making it difficult for non-native speakers to fully appreciate the depth of the stories.

Untranslatable Nuances and Cultural Contexts:

Many aspects of Philippine mythology resist straightforward translation into English, as the stories are interwoven with cultural nuances and contexts specific to the Filipino experience. Terms like "kapwa" (shared identity) or "pakikipagkapwa-tao" (social relations) carry layers of cultural meaning that elude easy translation. Attempting to comprehend these nuances without a deep understanding of Filipino culture can result in a superficial interpretation that fails to capture the richness and complexity of the mythological tales. Only native speakers can fully grasp the meaning and context, with excemption to foreign Anthropologist who have studied and learned can speak and fully comprehend the language

Killing the Living Mythology of Philippines in modern times

Eurocentric Perspectives (Foreign gaze)and Imposition:

Eurocentrism, rooted in a Western way of thinking, may impose preconceived notions and frameworks onto Philippine mythology. The tendency to view these narratives through the lens of European mythologies can lead to a reductionist interpretation, overlooking the unique cultural and linguistic nuances that distinguish Filipino myths. This imposition risks eroding the authenticity of the stories, perpetuating a cycle reminiscent of historical colonization.

Static vs. Dynamic Nature of Myths:

The living and orally passed down nature of Philippine mythology contrasts sharply with the static representations often found in Western mythologies. Foreign perspectives, shaped by exposure to written and fixed narratives, may struggle to grasp the dynamic nature of myths that evolve with each oral transmission. Attempts to freeze these narratives in a rigid framework can stifle the organic growth and adaptation inherent in the living tradition.

Gatekeeping and Cultural Hegemony:

Gatekeeping, whether intentional or unintentional, occurs when individuals or institutions control access to and interpretation of cultural knowledge. The imposition of Eurocentric gatekeeping in the study and dissemination of Philippine mythology can perpetuate a cultural hegemony that marginalizes indigenous voices and perspectives. This exclusionary approach hampers the preservation of the living tradition and stifles the authenticity of the narratives.

Historical Parallels:

Drawing parallels with historical colonization, particularly the Spanish occupation of the Philippines, underscores the danger of repeating the mistakes of the past. The Spaniards, driven by political and economic motives, imposed their culture, religion, and language on the indigenous population, leading to the destruction of ancestral beliefs and practices. Similarly, foreign perspectives that undermine the living nature of Philippine mythology risk contributing to the erosion of cultural heritage

Linguistic and Cultural Misinterpretation:

Foreigners, casual observers, may inadvertently misinterpret and distort Philippine mythology due to linguistic and cultural barriers. The nuanced meanings embedded in myths, carried through indigenous languages, often elude translation into Eurocentric frameworks. As outsiders attempt to understand and categorize these narratives through a Western lens, the depth and richness of the myths may be lost, resulting in a skewed representation that fails to capture the essence of the living tradition.

The perilous intersection of gatekeeping, Eurocentric perspectives, and a lack of understanding of the dynamic nature of Philippine mythology poses a significant threat to its preservation. As with the historical atrocities committed by colonial powers, the inadvertent imposition of foreign ways of thinking can contribute to the erosion of this living tradition. To safeguard the richness of Filipino mythology, it is essential to approach it with humility, recognizing the unique cultural and linguistic nuances, and amplifying the voices of the indigenous communities who hold the key to its authenticity and continuity.

Preserving the Heritage:

As globalization permeates every facet of life, the preservation of linguistic and cultural heritage becomes imperative. Fluent speakers of Philippine languages play a pivotal role in safeguarding the richness of their mythology, ensuring that future generations can access the profound insights embedded in the stories that have shaped their collective identity.

Preserving linguistic and cultural heritage is crucial for understanding and appreciating Philippine mythology. Fluent speakers of Philippine languages play a pivotal role in safeguarding the richness of these narratives, ensuring that future generations can access the profound insights embedded in the stories that have shaped the collective identity of the Filipino people. Foreigners, lacking the linguistic and cultural context, may struggle to navigate and fully appreciate the intricacies of this living tradition. But with love and dedication to learn the languages and the symbolic meaning of things one can fully understand the lessons and value of the myths and legends.

Philippine mythology is a treasure trove of cultural heritage, intricately woven into the languages spoken across the archipelago. To truly understand its depth and significance, one must embark on a linguistic and cultural odyssey, appreciating the nuances that resist easy translation. As the guardians of this living tradition, Filipinos hold the key to unlocking the profound insights embedded in their mythological narratives, reminding the world that the beauty of these stories can only be fully grasped through the languages of the Philippines.

REMINDER

The orally transmitted mythology of the Philippines is intended for sharing and understanding, not for appropriation, commercial exploitation, or the promotion of foreigners and foreign products. It is a dynamic narrative tradition that evolves over time, distinct from the standardized mythologies found in Western and European cultures. Unlike these established mythologies, the Philippine government has not mandated standardized versions of stories and legends.

Orally transmitted stories undergo variations and evolve over time, resulting in numerous different versions. There are many different version told by Filipinos,and retold by Filipinos.

.jpg)