Bicolano Myths

Sunday, October 5, 2025

Tuesday, September 23, 2025

Monday, September 15, 2025

Marhay na aldaw Bicolandia!

Marhay na aldaw Bicolandia!

📍 𝗠𝗮𝘆𝗼𝗻 𝗩𝗼𝗹𝗰𝗮𝗻𝗼, 𝗔𝗹𝗯𝗮𝘆, 𝗣𝗵𝗶𝗹𝗶𝗽𝗽𝗶𝗻𝗲𝘀

Beautifully captured by Raymund Moran

📸 Raymund Moran

Friday, September 12, 2025

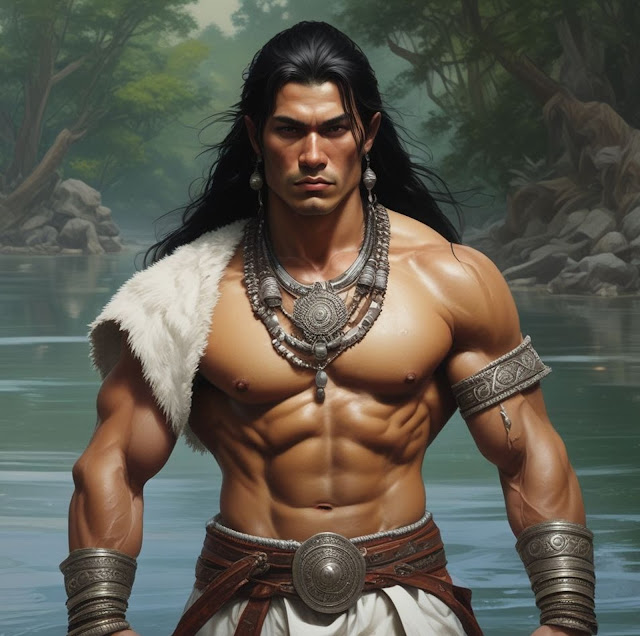

Puting Gabunan

The Puting Gabunan is a rare type of aswang in Philippine mythology. According to traditional stories, it was born from the forbidden love between a diwata (nature spirit) and an aswang. Some versions say a male diwata fell deeply in love with a female aswang, while other stories say it was the aswang who desired the diwata. From this unlikely union came children who were different from ordinary aswang. These beings became known as the Puting Gabunan, and the diwata and aswang couple are considered their ancestors.

Unlike most aswang, who are known for harming or eating humans, the Puting Gabunan usually do not attack people. Because they carry the blood of a diwata, they are naturally inclined toward goodness. In many stories, they are even seen as allies of humans, fighting against evil aswang. In their aswang form, they are described as tall, large, and extremely strong, with long white hair that seems to glow in the dark. Other aswang fear them because of their great strength and their brutal fighting ability.

Some stories, especially in more modern times, describe the Puting Gabunan as resembling white lycanthropes or white werewolves. This image is sometimes linked to Spanish and Western influence. Other explanations say this wolf-like form comes from their diwata blood. In folk stories, male diwata are often shapeshifters who can turn into white owls or white dogs. When this shapeshifting ability mixes with aswang blood, it results in the wolf-like or lycanthrope form of the Puting Gabunan.

The Puting Gabunan possess unusual powers inherited from both sides of their bloodline. They are far stronger than ordinary aswang and are known for their courage and cruelty in battle. They also have resistance to magic and are not easily affected by curses or sorcery. Most importantly, they have an inner moral sense and usually choose to protect humans rather than harm them. However, because they are born from both diwata and aswang, they are not fully accepted by either world. Aswang fear them because they are powerful and do not follow traditional aswang behavior, while diwata hesitate to accept them due to their connection to darkness.

Stories say the Puting Gabunan have a strong connection to the moon. This link reflects their mixed blood. Aswang are associated with night and darkness, while diwata are tied to nature and light. The Puting Gabunan stand between these two forces. When the moon shines, especially during a full moon, their strength increases. From their diwata side, they gain power from the moon’s light, which symbolizes purity and balance. From their aswang side, their strength and form are affected by the night.

Because of this, many believe the moon helps balance their nature. The Puting Gabunan do not fully fall into darkness like other aswang, but they also cannot return completely to the light of the diwata. This balance defines who they are.

In legends and folktales, the Puting Gabunan are often portrayed as solitary beings. They usually have no tribe and no allies of their own kind. Many stories describe them as lone protectors of humans, fighting monsters and evil spirits. Yet because they are half-aswang, they are never fully welcomed by the diwata. This is why they are often shown as wandering warriors traveling alone, fighting evil, but never truly belonging to either side.

In modern retellings, the Puting Gabunan are sometimes portrayed like heroic figures from films or fantasy stories. They are shown as powerful, mysterious beings who represent hope—the idea that even in a world filled with darkness, goodness can still exist.

Friday, August 15, 2025

Monday, July 21, 2025

Ang Alamat ng Lawa ng Bulusan

Maraming ibat ibang kwento ang Lawa ng Bulusan, gaya ng Si Bulusan nan Si Aguingay ang magkasintahan. Mayroon din naman ay tungkol kay Datu Bulan isa pang kwento ukol sa lawa. May mga nagsasabing ang Bulusan Lake ay dugo ng ibong Dambuhalang Mampak, at ang San Bernardino Island ay kung saan ito inilibing.

Maganda at kahanga-hanga ang Lawa ng Bulusan. Ito ay nasa tuktok ng bundok at napaliligiran ng malalagong punung-kahoy. Malinaw at malalim ang Lawa ng Bulusan. Isa ito sa mga magaganda at kilalang pook sa Kabikulan kaya ito ay ipinagdarayo ng mga turista taon-taon. Saan nagmula ang Lawa ng Bulusan? Ganito ang kuwento ng matatanda sa nagpapaliwanag ng pinagmulan ng maganda at kahanga-hangang lawa sa tuktok ng bundok. Noong unang panahon, si Datu Bulan ay kilalang kilala sa buong Kabikulan dahil sa kaayusan niyang gumamit ng busog at pana. Nakilala rin siya bilang mabuting puno ng kanyang nasasakupan. Matagal ding panahong naging masagana, mapayapa at maligaya ang mga katutubong nasasakupan ng datu hanggang sa dumating isang araw ang isang malaki at maitim na ibon sa kanilang pamayanan. Mula na noon nangamba ang mga tao sapagkat tuwinang umaga ay nakikita nila ang kakaibang ibon na umaaligid sa kanilang pamayanan. Nagkaroon ng takot ang mga katutubo nang mapansin nilang nagiging mababa ang lipad ng maitim at malaking ibon. Inisip nilang baka na lamang dagitin ng malaking ibon ang maliliit na mga bata na di mapigil sa paglalaro sa kani-kanilang mga bakuran. Dahil sa ganitong pangyayari, tinawag ni Datu Bulan ang kanyang matatandang tagapayo at sila ay nagpulong. Napagkaisahan nila sa kanilang kapulungan na patayin ang ibon. Noon din ay tinawag ni Datu Bulan ang lima sa pinakamahusay niyang kawal sa paggamit ng busog. Sila ay pinapaghanda ng datu. Kinabukasan, maagang lumakad ang pangkat patungo sa gubat upang hanapin ang malaki at maitim na ibon. Kaagad nilang nakita ang ibon nakadapo sa sanga ng malaking punungkahoy. Nang makita sila ng ibon ay lumipad ito patungo sa kanila at nagpaikot-ikot sa kanilang ulunan. Sabay-sabay na tinudla ng pana ng mga kasamang kawal ng datu ang ibon. Si Datu Bulan naman ang naghanda ng kanyang busog at pana. Kanya itong pinakawalan at Tsok! Tamang-tama sa dibdib ang malaki at maitim na ibon. Ngunit nagpatuloy nang paglipad ang sugatang ibon hanggang sa makarating ito sa maliit na lawa. Naging kulay pula ang tubig ng lawa. Nang di na makatagal ang ibon, ito ay bumagsak sa lawa at kitang-kita ng datu at ng kanyang mga kasamang kawal na nawala at sukat ang malaki at maitim na ibon na waring hinigop ng tubis sa lawa. Unti-unting lumaki ang tubig hanggang sa kasalukuyang laki nito ngayon. Nalaman ng mga katutubo ang kinasapitan ng malaki at maitim na ibon at ang paglaki ng dating maliit na lawa. Mula noon, tinawag ng mga tao ang katawan ng tubig sa tuktok ng bundok na Lawa ng Bulusan. Ang ibig sabihin nito ay tubig na inagusan ng dugo.

Sa tuktok nin bukid, tahimik na naglalayag,

An Lawa nin Bulusan, malinaw asin marhay.

Palibot kagsa-kagsa, punong kahoy naglililim,

Lahi nin paraisong sa Kabikolan yaon an giting.

Mayo pang magtatao sa gandang pinapagalang,

Kaya mga bisita, taon-taon nagdadagsa man.

Pero may istoryang sa laog may tinatago,

Pag-orog sa siring nin sining kaanyag na lugar ko.

Kuwento nin gurang, istorya nin kaaraman,

An pinagbuhatan kan lawa, pakinggan ta siring maray.

Si Datu Bulan, datung mapanahon,

Busog asin pana, sa kamot an taramon.

Maginabangon, igwang pagkamuot sa sakop,

Pinagpapahingalo an kabukidan, laog nin pag-idop.

Dagos an katahunan, uran asin araw,

Muntilog an mga tawo, nagpapahingalo, payapa an law.

Pero minabot an ibon dakula, itom, mapang-imbabaw,

Naglipad sa langit, an mga aki nagtagò, nagininalang.

"Ay, bako ini basta lang hayop," sabi nin gurang,

"Baka kinukuha an aki, sa langit idadarang!"

Dagos nagpulong si Datu, mga pinagtutubò tinawag,

Kinakaipuhan an sala, si ibon dapat madakop,

Nagdara nin busog, lima an pinili mga kawal na halang ang bituka,

Pagkaaga pa, sa kakahoyan, sa laban nagsadulok.

Sa sanga nin kahoy, si ibon nagpapahingalo,

Pero sa pag-abot kan mga kawal, nilipad ini paibaba,

Nagpaikot sa saindang ulo, may gahum, may lakas,

Kaya sabay-sabay tinudla! Pana nagpadaog sa hangin nin bukas.

Si Datu Bulan, nag-abang nin tsansa,

Pinakawalan an pana, sa dibdib igwa nin tama!

Nagkurog si ibon, pero naglipad padagos,

Hanggang sa dakulang huring lugar sa may lawa, an pagtugos.

An tubig, dating malinaw, nagkulay pula,

Para bang dugo an nabubo, siring salang dakula.

Si ibon, nalubog, nawara, waring sinupsop,

An lawa, nagdakul... dakul pa lalo, tubigon nagdarakop.

Kaya ngonian, an mga tawo nagtaram,

“An Lawa nin Bulusan,” iyo an tinawag, an panganiban.

Tubig na pinag-agasan nin dugo, siring hinibi kan kasaysayan,

Na sa puso nin Kabikolan, dae malilingawan.

Bulusan Lake is a beautiful and famous lake on top of a mountain in the Bicol region. This is one of the many legends of the origin of the Lake, Long ago, a powerful datu named Datu Bulan protected his people. One day, a large black bird appeared and scared the villagers.

Afraid the bird would harm the children, Datu Bulan and his best warriors hunted it. Datu Bulan shot the bird with an arrow, and it flew to a small lake. The bird fell into the water, and the lake turned red. Then, the bird disappeared, and the lake grew bigger and bigger.

Since then, people have called it Lake Bulusan, which means “lake where blood flowed.”

Ang Prinsipeng Isinumpa

Ang Prinsipeng Isinumpa

Noong unang panahon, sa isang magandang lungsod na malapit sa masukal na gubat, ay may isang makapangyarihang Datu na napakayaman. Ang gubat na ito ay tirahan ng maraming masasamang engkanto at mangkukulam.

May anak ang Datu na nagngangalang Prinsipe Ukay. Siya ay matapang, matalino, at gwapo. Ngunit lihim siyang umiibig sa isang magandang dalagang mangkukulam, anak ng pinakamatinding kaaway ng kanyang ama.

Nang dumating na ang panahon para mag-asawa si Prinsipe Ukay, gusto ng Datu na piliin niya ang pinakamagandang dalaga sa kanilang lungsod. Pero ayaw ni Ukay. Hindi niya kayang sabihin sa kanyang ama ang tungkol sa kanyang pag-ibig sa dalagang mangkukulam.

Dahil dito, pinilit ng Datu ang kanyang anak. Pinapili niya ito ng mapapangasawa, at dahil hindi pumili si Ukay, siya na mismo ang pumili ng isang maganda at maayos na dalaga para ipakasal sa prinsipe. Dahil sa takot at hiya, pumayag si Ukay, kahit hindi ito ang kanyang tunay na mahal.

Galit na galit ang dalagang mangkukulam nang malaman ang kasal. Dahil sa sama ng loob, isinumpa niya ang buong lungsod! Ginawa niya itong isang malawak at magandang gubat.

Ang prinsipe, ginawang isang unggoy, at ipinatira sa pinakamataas na punongkahoy. Sabi ng dalaga,

“Mananatili kang unggoy sa loob ng limang daang taon, maliban na lang kung may isang magandang dalaga na mamahalin ka nang tapat at higit pa sa kahit ano pa man.”

Ang mga tao sa lungsod? Ginawa rin niyang iba’t ibang hayop!

Lumipas ang apat na raang taon, at unti-unting nakalimutan ng mga tao ang tungkol sa mahiwagang lungsod. May mga nagsimulang tumira sa lugar, nagtayo ng mga bahay, at maging ng simbahan malapit sa punongkahoy kung saan nakatira ang unggoy na prinsipe.

Dalawang babae na ang nadala ng prinsipe sa itaas ng puno, ngunit namatay sila sa takot. Kaya malungkot pa rin si Prinsipe Ukay, naghihintay ng tamang panahon at ng tamang dalaga.

Isang Linggo ng umaga, habang may misa sa simbahan, isang magandang dalaga ang lumabas. Siya’y anak ng isang mahirap na ama, at kasalukuyang malungkot, dahil iniwan siya ng minamahal niyang lalaki isang anak ng mayaman na piniling pakasalan ang anak ng isa pang mayaman.

Dahil sa matinding lungkot, umupo siya sa paanan ng punongkahoy at nagdasal, halos gustong sumuko.

Tahimik na bumaba ang unggoy at hinawakan ang kamay ng dalaga. Dinala siya sa itaas ng punongkahoy. Akala ng dalaga ay katapusan na niya, pero nang makita niya ang malungkot ngunit marangal na mga mata ng unggoy, hindi siya natakot. Sa halip, naawa siya, at unti-unting minahal ito.

Araw-araw, pinakain siya ng masasarap at mahiwagang prutas, at habang lumilipas ang mga araw, mas minahal pa niya ang kakaibang nilalang.

Sa ikasampung gabi ng kanilang pagsasama, nagising ang dalaga sa loob ng isang palasyong maganda at makinang. Sa tabi niya ay isang guwapong prinsipe si Prinsipe Ukay!

Sabi ng prinsipe,

“Salamat sa iyong tunay na pag-ibig. Ikaw ang tumapos sa aking sumpa.”

Kinabukasan, ginawa siyang Reyna ng kaharian. Ang mga dating hayop ay naging tao muli, at nagdiwang ang buong bayan!

At mula noon, si Prinsipe Ukay at ang kanyang mapagmahal na reyna ay namuhay nang masaya at mapayapa, minamahal ng lahat, habang-buhay.